By Theodore Shoebat

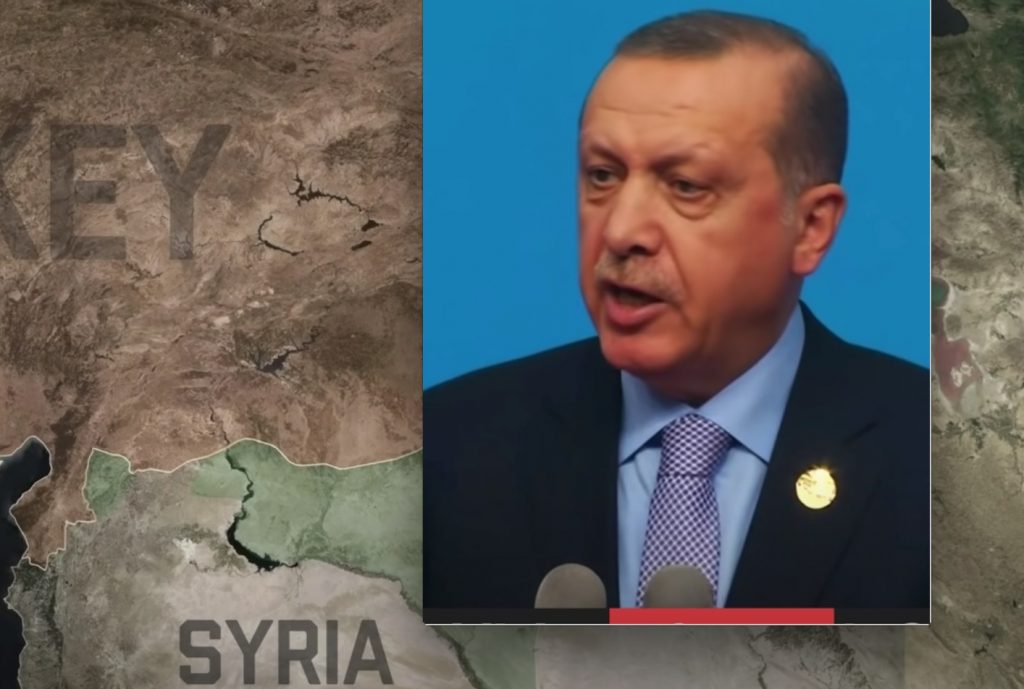

In July of 2016, there was a failed coup against Erdogan. In the next morning, Erdogan declared: “This uprising is a gift from God to us because this will be a reason to cleanse our army.” And this is exactly what happened. Soldiers and high ranking officers were accused of being a part of a conspiracy with the Islamist Gulen movement, the arch enemy of the Erdogan regime. By December of 2016, the number of Turkish military personal was reduced by a third, and the number of generals and admirals was dropped by almost half. With this major reduction of Turkish soldiers, the military became purged of people who were more resistant to Erdogan’s agenda. Soldiers who were more loyal to the AK Party’s policies now dominated, which meant there was no impediment to government actions. Those generals who survived the purge were quite enthusiastic to show their allegiance to Erdogan and support his policies.

The generals who were pro-NATO were being overridden by generals who wanted Turkey to become closer to Russia as opposed to the American sphere of influence. Hence why we see Russia and Turkey collaborating in Nagorno-Karabakh. This purge of the generals enabled the Erdogan regime to pursue its military entrance into Syria. An invasion of Syria was something that many of the generals resisted, but now that these were removed, the policy could be executed without hinderance. “The generals who survived the 2016 purges were determined to show their loyalty to the regime,” writes Francesco Siccardi, “for example, by intervening in Syria, a policy they had long opposed in the past.” It is not surprising, then, that in August of 2016, the month right after the failed coup, Turkey commenced its invasion of Syria under the title of “Operation Euphrates Shield.” It was done (supposedly) for the purpose of crushing ISIS and repulsing Kurdish forces. The US government’s support for the Kurds is what triggered Turkey to enter Syria. The Americans believed that the Kurds were the most reliable force to use as a proxy against ISIS. The negative effect of helping the Kurds on the US’s alliance with Turkey was not taken into serious consideration. In order to push the Americans to abandon the Kurds, Turkey started a war with them, and the US would eventually leave the Kurds at the mercy of an invading Turkish force. In the words of Carnegie Europe:

“The United States’ difficulty in keeping Kurdish forces under control—in the Syrian town of Manbij in the summer of 2016, for example—was one of the triggers of Operation Euphrates Shield. From January to March 2018, Operation Olive Branch was partly aimed at deterring the United States from backing the PYD.”

But, in 2018, Turkey started another mission in Syria — “Operation Olive Branch” — which was being done to remove the Kurdish militia, the People’s Defense Units (YPG) from the Afrin Canton. However, there was another objective in Operation Olive Branch, and that was (according to Carnegie Europe) to “Rebuild the Turkish army’s morale and restore Turkey’s confidence in its military”. So while the Turkish government wanted to vanquish and purge out Kurdish paramilitaries, it also wanted to boost and reinvigorate the Turkish people’s faith in, and exuberance for, the military. Syria was thus the testing ground to reanimate Turkey’s militarist culture and to demonstrate the country’s capacity for empire. This idea proved successful. Turkey — glorying in its own strength and the awe the world would give it — would expand itself to the South Caucasus, to Nagorno-Karabakh where the earth would witness Turkish drones slaughtering Armenians.

In order for militarism to have the backing of the masses, there needs to be an enemy. In this case, the enemy was the Kurds. And so by pursuing military action against the Kurds, the government has the energy of the people. Another factor for successful militarism is nationalism, and this is something that Erdogan’s regime — regardless of its universalist Islamism — has had to utilize. Erdogan’s success in Syria has garnered for him favor from Turkish nationalists. In connection to this Islamist-nationalist alliance, it is essential that we briefly explain how Erdogan’s Islamist AK Party ended up forming a coalition with the far-Right Turkish organization, the Nationalist Movement Party or MHP. This coalition formed as a result of the AK Party’s rivalry against the far-Left, pro-Kurdish and pro-minority organization, the People’s Democratic Party (HDP). In June of 2015 — for the first time since 2002 — support for the AK Party declined and did not have the majority presence in the parliament that he desired. This was due to the growing popularity of the HDP which had won 13% of the vote and became the second largest opposition party (right after the nationalist CHP). With the rise of the HDP, Kurdish politicians now posed a threat to Erdogan’s pursuit to increasing the power of the presidency. This had to be squashed to remove any impediments to Erdogan’s will to power.

A propaganda strategy had to be utilized, and pro-Erdogan media began to report about how the HDP was connected with the Left-wing terrorist group, the Kurdish Worker’s Party or PKK. The strategy was effective and in November of 2015, voters gave the parliamentary majority that Erdogan wanted. But, it wasn’t enough to give Erdogan the executive power he wanted (a constitutional referendum requires three-fifths of the parliament to succeed). Nonetheless, Erdogan had enough to establish an AK Party-led government. Erdogan did not cease in his campaign against the PKK and YPG. He wanted to convey the message that his political rival, the HDP, was the same as the PKK and the YPG. For the eighteen months after the November 2015 election, the AK Party-controlled government used all of its power to impede the influence of Kurdish politicians. HDP lawmakers were detained on charges of disseminating terrorist propaganda. But the reality was that much of what these politicians were saying was that the Turkish administration was supporting ISIS, and for stating this they were arrested and confined. These arrests were enabled in May of 2016 by a parliamentary vote to strip HDP members of parliament of their immunity from prosecution. Sentiments against Kurdish militants were intensified even more when, in August of 2016, Turkey entered Syria to fight against Kurdish paramilitaries.

The government devastated the HDP in November of 2016 when it had two of its leaders, Demirtas and Figden Yuksekdag, arrested and charged with terrorist propaganda. The AK Party then needed another party to make a coalition with so as to get its referendum to raise the presidential power. This led the AK Party to form a new alliance with the far-Right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). The move opened the door for Erdogan to a new, nationalist audience. And what type of audience is the MHP and its followers? In July of 2015, during tensions between Turkey and China over treatment of the Uighurs, there was a wave of violence against Korean tourists in Turkey because they looked Chinese. Members of the fascist organization, the Grey Wolves, carried out the attacks and hung a banner at their Istanbul headquarters with the words: “We crave Chinese blood”. The leader of the MHP, Devlet Bahceli, downplayed the incidents by saying: “These are young kids. They may have been provoked. Plus, how are you going to differentiate between Korean and Chinese? They both have slanted eyes. Does it really matter?” MHP’s ideology is one of nationalism and Islamism merged together in a sort of synthesis. This is embodied in one of its slogans: “Our bodies are Turkish, our souls Islamic. A body without a soul is a corpse”.

Turkey’s militarist expansion into Syria must be seen in the context of its nationalist surge. Operations Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch were absolutely essential to stoking up the support of far-Right nationalists that Erdogan needed. It all worked in his favor. In April of 2017 the constitutional referendum was approved (with a thin majority of 51 percent of the vote of Turkish citizens) leading to the abolishing of the office of prime minister, and the president was given more control over appointments to the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK). In March of 2018, Turkey landed its military victory over the Kurdish forces in Afrin, further establishing Turkey as a major military power and increasing the wave of nationalist fervor for Erdogan.

Turkey’s military operations in Syria did several things: while it reinvigorated the Turkish people’s fervor for militarism, it raised an awareness for nationalism, it also gave the Turkish military experience in the battlefield, and allowed Turkey to test and demonstrate its military capabilities. In the words of Carnegie Europe: “In all these respects, Turkey has used Syria as a test case and a training ground.”

Turkey also showed the world the effectiveness of its combat technology, specifically multibarrel rocket-launcher systems, air-to-ground precision-guided munitions, and drones. The destructiveness of such drones would be fully witnessed by the world in 2020 at Nagorno-Karabakh where these Turkish machines of death wreaked havoc and enabled the Azeris to prevail over Armenian soldiers. The demonstration of Turkish drones boosted the demand to purchase them. Thus, Turkey’s operations in Syria led to the rise in its defense industry. In 2002, Turkey’s industry’s exports was worth $248 million, and in 2019 it went up to $3 billion, with countries like Poland, Qatar, and Ukraine purchasing Turkish drones. As we read in Defense News:

“The Ukrainian government announced Sept. 15 that it’s seeking 24 Bayraktar TB2 combat drones in the coming months. Two years ago, TB2 producer Baykar Makina won a contract to sell six TB2s to Ukraine. The $69 million contract also involved the sale of ammunition for the armed version. The private firm has also won contracts to sell the TB2 to Qatar, Azerbaijan and Poland.”

In the summer of 2018, Turkey wanted to do another military operation in Syria, and began to pressure Washington to be allowed to do so. In December of 2018, president Donald Trump announced the US’s withdrawal from Syria:

“We’ll be coming out of Syria, like, very soon. …Let the other people take care of it now. Very soon, very soon, we’re coming out … We’re going to get back to our country, where we belong, where we want to be.”

Whats interesting is that this announcement was made after Trump had a phone conversation with Erdogan. This is not surprising since in March of 2018 Trump spoke with French president Emmanuel Macron about deepening cooperation with Turkey in Syria. As a Whitehouse statement explains:

“President Donald J. Trump spoke today with President Emmanuel Macron of France. Both leaders expressed support for the West’s strong response to Russia’s chemical weapons attack in Salisbury, United Kingdom, including the expulsion of numerous Russian intelligence officers on both sides of the Atlantic. President Trump stressed the need to intensify cooperation with Turkey with respect to shared strategic challenges in Syria.”

In October of 2019 Turkey commenced “Operation Peace Spring”, and in just a matter of days the Turkish military and its proxies were able to conquer a 62 mile strip of land between the border towns of Tel Abayad and Ras al-Ain and repulsed the YPG out.

Writing on the rise of Turkey would be quite lacking if we did not at least mention the country’s work and tensions with Russia. They will have diplomatic ties (such as in the Astana agreement) but at the same time there has been violence between them. Russia and Turkey are rivals (they have historically been enemies), and all the while they will use each for their own geopolitical ends. When Turkey was going to war with the Kurds in Syria (in Operation Euphrates Shield), the head of the Syrian Kurdistan Region, Rodi Osman, called on Russia to put pressure on Turkey and stop shelling Kurdish areas. But, Moscow did not intervene. Russian analysts believe that Operation Euphrates Shield was agreed upon by both Putin and Erdogan in St. Petersburg. In return, Erdogan promised Putin help in the fight against jihadists from Jabhat al-Nusra in Aleppo.

In Libya, Turkey backed the NATO proxy Government of National Accord, while Russia supported its enemy, Khalifa Haftar. In 2019, Russia and the Syrian government joined forces to fight Turkish backed rebels in the Idlib provence. In early 2020, Turkish troops fought to take territory specifically along the M4 and M5 highways and at their intersection in Saraqib, an important junction for controlling northern Syria. Violence between Turkey and Russia really manifested in February of 2020 when the Moscow backed Syrian air force slaughtered at least 34 Turkish troops in the village of Baylun. Turkey did not point the finger at Russia, but it did militarily respond to the Syrian government by launching Operation Spring Shield in order to stop the Assad regime’s advance on Idlib.

Eventually there was a ceasefire between Ankara and Damascus made in March of 2020, negotiated by Erdogan and Putin. Although Turkey lost its advance by agreeing to the ceasefire, it still got to control most of the Idlib Governorate, thus enabling Turkey to maintain a foothold in the region. It also further established Turkey’s position of influence over Syria’s future. Regardless of the ceasefire, violence still occurred. In October 26th of 2020, Russian fighter jets struck and slaughtered 78 members of Failak al-Sham, a rebel group that is being backed by Turkey.

Failak al-Sham’s kept a strong presence in Idlib in order to maintain Turkey’s foothold in the provence, and representatives of the rebel group were even involved in the peace talks in Astana. Erdogan reacted sharply to Russia’s attack: “The Russian attack on the forces of the Syrian national army in Idlib shows that they do not want long-term peace and tranquility in the region.” Strangely, not long before this strike took place, Putin praised Erdogan for pursuing an independent foreign policy; and a few days earlier before this, Erdogan received the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise from Ukrainian President Zelensky for “supporting the independence and territorial integrity of Ukraine.” Ukraine honored Erdogan for his support of Crimea against the Russian annexation. “Turkey does not and will never recognize the ‘annexation’ of Crimea” Erdogan once said.

But, while there are tensions between the two countries, there is collaboration. Russia and Turkey need each other at this time; Russia needs Turkey because it is the dominating Islamic power in the Middle East and thus cannot be ignored in the negotiating table. By working closer with Russia, Turkey is defying the United States, and is thus defying, and declaring its own independence of, American power and control — something that Russia desires. This was seen in Turkey’s purchasing of the Russian missile system, the S-400, and conducting tests of the weapon, which greatly exasperated American-Turkish relations. Regardless of American pressure, Erdogan continued in his defiance of the American empire, declaring:

“It is true that tests have been carried out … What are we supposed to do, not test these capabilities? Obviously we’re not going to ask the U.S. [for permission].” (Brackets mine)

What we are witnessing is a Turkish rebellion against the American empire. And now we see Turkey and Russia in Azerbaijan as a result of the recent war between Azeris and Armenians over Nagono-Karabakh. Turkey backed Azerbaijan and provided the drones that would slaughter and vanquish the Armenians, who the Turks tried to annihilate during World War One. So here we can see the connection between Turkey’s war in Syria and its war in Nagorno-Karabakh. As we said before, Syria provided the testing ground for Turkey’s military capabilities and its drones. These very drones would then be used to defeat the Armenians. Turkey in Syria marked the revival of its power, and after demonstrating its force and strength, it manifested its capacity for empire, thus giving Turkey the geopolitical position to expand itself in the South Caucasus. Russia is an ally of Armenia, but at the same time sees Azerbaijan as a strategic partner in the South Caucasus. Thus, Russia — not wanting to jeopardize relations with Azerbaijan — sees no purpose (at least for now) in resisting Turkey in this particular conflict. But, we cannot forget the reality of history: Turkey and Russia are historical enemies and have had numerous wars against each other. Diplomacy will continue on — for now — but if history is any indication, the Russian eagle and Turkish wolf will be caught up in a fray yet again.