By Theodore & Walid Shoebat

It was not enough to be wrong about the knowledge of God. They lived in a state of evil warfare, but they were so ignorant that they called it peace. — Wisdom 12:22

“For the amphitheater is consecrated to names more numerous and more dire than is the Capitol itself, temple of all demons it is. There are as many unclean spirits there as it holds men.” — Tertullian

How many martyrs died, how much Christian blood was spilt by cruel hands in the war to end paganism? And in just a matter of decades the forces of evil want to destroy the work of Christianity and have the earth return back to the hollow manners of pagan hysteria.

There has been a growing popularity for paganism. Those on the Left want to glorify Mother Earth; while those on the Right have a fascination with European paganism, glorifying Thor’s Hammer, and the Graeco-Roman world as holding an ideal “masculinity.” But what does such a fascination bring about? The glorification of strength, the hatred of Christ, the worship of death and the sacramentalizing of violence — these are the fruits of pagan evil. The fantasizer, entrenched in his darkness, will one day want his fantasy to become a reality. His idol is his fantasy, and the sacrifices it demands are in human blood. God tells Pharaoh: “I bring your destruction among the nations, into the countries which you have not known” (Ezekiel 32:9). Pharaoh’s religion — paganism — will spread to nations that do not know Egypt and it shall be in the kingdoms of the idols (Isaiah 10:10).

The result of paganization does not need to be wondered at greatly. All one has to do to see the denouement of paganism is to read the history of far antiquity. Ancient history is like a story book, reminiscing the ways that man always turns to and revealing the same outcomes. Why wonder about the end of current events, when you can read the chapters of history and know how the story ends? Paganism brings about savagery and slaughter, but in the end it is cut asunder by the unsheathed sword of justice. If you do not want the religion of the Carpenter, then you shall eat the carcass of Pharaoh, absorbing all of Egypt’s and Sodom’s ways, with their despotism, enslavement and abysmal spirits.

One of the best examples of pagan savagery is the gladiatorial matches.

When we think of the gladiatorial matches, we picture a form of cruel entertainment. What is almost never discussed is how the gladiatorial games had their origins in ritual human sacrifice. Tertullian, the third century Christian scholar, gives us the most detailed account on the origins of the gladiatorial matches to have survived antiquity. Tertullian tells us that the gladiatorial games descended from a ritual that came from a people called the Etruscans. These migrated from Lydia and moved to a northern part of Italy that we today know as Tuscany. This migration was not something unusual, given that there were many migrations from Anatolia to Italy at various points in far antiquity. The Romans were originally descendants of the Trojans who migrated from Anatolia after the sack of Troy and settled in Italy. In fact, much of Italy, at one point or another in antiquity, was settled by Anatolians and Greeks. The historian Justin writes on this in detail, telling us of how the Etruscans (or Etrurians) settled on the Tuscan sea after travelling from Lydia; how the Veneti settled on the Adriatic coast after coming from Troy; how Pisa and Liguria were settled by Greeks. So numerous were these migrations that, in the words of Justin: “all that part of Italy was called Greater Greece.” (Justin, Hist., book xx, 1-2) According to Tertullian, the Etruscans were led by Tyrrehenus and settled in Etruria.

They would bring their rituals with them, and that included human sacrifice. When a member of a family died they believed that they needed to make an offering of human blood to the spirits of the dead. The family would purchase captives or slaves (who were forced into slavery because of a supposed criminal background), and then, in the funeral, they would burn them alive as a burnt offering. This ritual would be later changed. Instead of immolating the victim, they would train these slaves or captives on how to use a sword and then have them fight to the death. The one who was slain would then propitiate the souls of the dead. “It was the custom”, writes Festus, “to sacrifice prisoners on the tombs of valorous warriors; when the cruelty of this custom became evident, it was decided to make gladiators fight before the tomb.” (See Auguet, Cruelty and Civilization, ch. 1, p. 21)

Human sacrifice was done for funeral rites in the ancient Mediterranean world and one can even see this in the infamous book, the Iliad, in which Achilles slits the throats of twelve young Trojans for the funeral rites of Patroclus after he was killed while fighting in the invasion of Troy. As Homer’s epic says: “Before your funeral pyre I’ll cut the throats of twelve resplendent children of Trojans — that is my murdering fury at your death.” (Iliad, book 18.393-395). Later on the Iliad — which reads more like a record of war crimes than a story to be proud of — Homer recounts:

“But soon as Achilles

grew arm-weary from killing, twelve young Trojans

he rounded up from the river, took them all alive

as the blood-price for Patroclus’ death, Menoetius’ son.

He dragged them up on the banks, dazed like fawns,

lashed their hands behind them with well-cut straps—

their own belts that cinched their billowing war-shirts—

gave them to friends to lead away to the beaked ships

and back he whirled, insane to hack more flesh.” (Book 21)

There is a 4th century BC Etruscan tomb painting from Vulci depicting Achilles slaughtering a young Trojan, a reflection of how such rituals permeated the culture.

And its not as if this did not have parallels with the Aztec Empire, with Achilles rounding people up and tying their hands behind them so that they can be sacrificial victims. But this was the way of the world under the terror of paganism’s reign. While the gladiatorial games were rooted in ritual and marketed with pomp and entertainment for the masses, cruelty was at the heart of it all. When a gladiator lost, and was on the ground, he waited for the decision to be made to either be killed or spared. When death was demanded the editor — the one who financed the match — would put his thumb down and shouted: “Jugula!” which means “Cut his throat!” The loser would passively hold onto the thighs of the victor, putting one knee on the ground, as if to respectively accept his fate. Any sort of weakness expressed by the one who was about to die received contempt. “We hate those weak and suppliant gladiators,” said Cicero, “who, hands outstretched, beseech us to let them live.” There was a saying engraved on the walls of the gladiators’ barracks: “Ut quis quem vicerit occidat.” “Kill the vanquished whoever he may be.” (See Auguet, Cruelty and Civilization, ch. 2, pp. 50-51, 58).

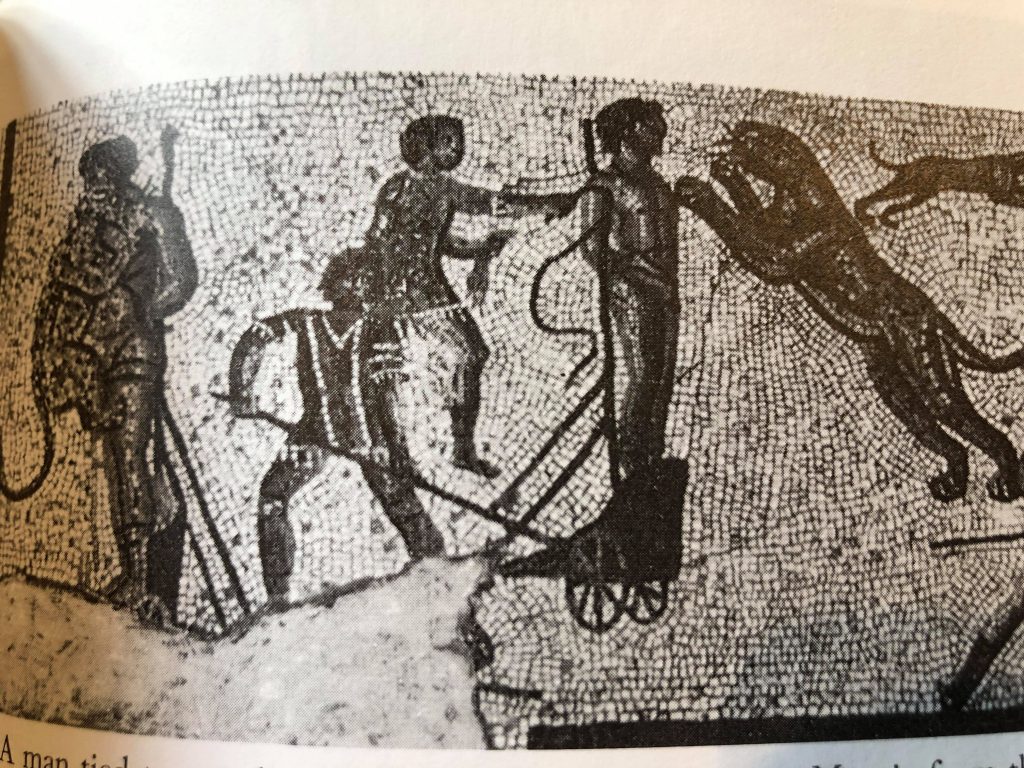

Criminals, slaves and captives continued to be victims in these horrid events, just as it was when the Etruscans were committing these same cruel rituals in Etruria. There was even a punishment in Rome called noxii ad gladium ludi damnati, or condemned to the sword in the amphitheater. Two criminals were forced into the arena; one was given a sword and one was unarmed. At the commencement of the bloody rite, the one who had no weapon fled only to be met with guards armed with whips and branding irons who’d force him into his slaughter. Once he was butchered, the one with the knife was disarmed and forced to fight another victim who was, this time, the knife carrier. This was repeated over and over again, until there was just one man left who was then disarmed and his throat slit, just as the Etruscans slit the throats of their victims for their funeral rites. Seneca witnessed this slaughterhouse and recounted what disturbing growls he heard from the foaming and rabid crowd who watched on with viciousness: “Kill him! Lash him! Burn him! Why does he meet the sword in such a cowardly way? Why does he strike so feebly? Why doesn’t he die game? Whip him to meet his wounds! Let them receive blow for blow, with chests bare and exposed to the stroke!”

The human sacrifice of the Mediterranean peoples is not only found in ancient books, but in archeology as well. There are tomb paintings from the 6th century BC made by the Etruscans (who Tertullian tells us brought into Italy the ritual that would eventually become the gladiatorial matches). In one tomb painting there is a blindfolded man being attacked by a dog. Next to the victim is a masked figure named Phersu (whose name means “masked man”) who is armed with a whip or leash.

The Etruscans, as we also learn from Tertullian, fed their victims to animal alive as part of this system of ritual murder. To quote Tertullian:

“But by degrees their refinement came up to their cruelty; for these human wild beasts could not find pleasure exquisite enough, save in the spectacle of men torn to pieces by wild beasts. Offerings to propitiate the dead then were regarded as belonging to the class of funeral sacrifice; and these are idolatry: for idolatry, in fact, is a sort of homage to the departed; the one as well as the other is a service to dead men.” (De Spectaculis, ch. xi)

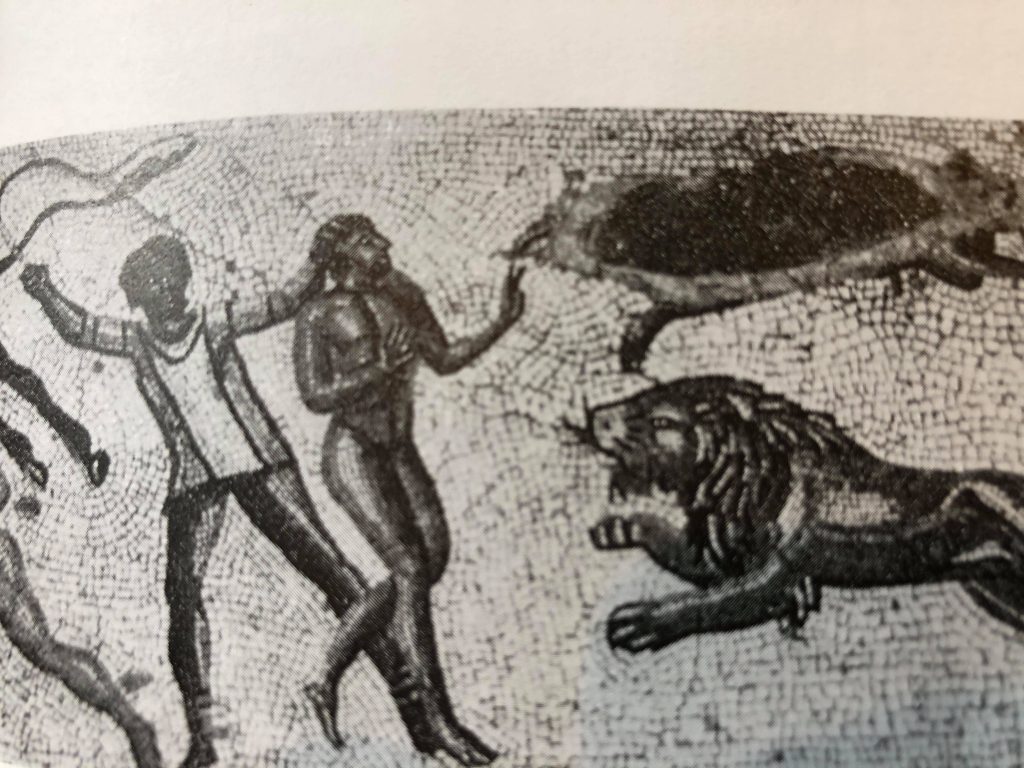

Feeding victims to animals was continued by the Romans, as we have all heard about how Christians were fed to lions for the entertainment of the mob. “In the morning,” says Seneca, “they throw men to the lions and bears; at noon, they throw them to the spectators.”

The Etruscan origins of the gladiatorial matches were so deep that the Romans called the games, Ludi, denoting the Lydian source of the ritual (since the Etruscans came from Lydia). The ritualistic nature of the gladiatorial matches were also signified by the fact that the Romans called a match Munus (Munera as plural) which means “duty” or “obligation.” Tertullian refers to it as “a dutiful service”. A dutiful service to whom? To the gods. As Tertullian explains, the games (ludi) were instituted “in honor of the idol-gods of the nations or of the dead.” (De Spectaculis, ch. xi). Hence why the games were also referred to as “Olympian”, in honor of the god Jupiter. The games — be it the death matches or the chariot races — were all called ludi, and thus did they have the same religious origin.

In the Circus Maximus — the main chariot racing arena — there was an array of idols. There were, for example, three altars dedicated to Great, Mighty and Victorious. There was also an Obelisk dedicated to the Sun, which was something learned by the Romans from the Egyptians. The eggs that were used to represent the completion of each lap were regarded as sacred to Castor and Pollux, both chariot riding deities. The images of dolphins, also used to mark completed laps, were in dedication to Neptune, the god of the sea. The field on which the Circus Maximus was built was dedicated to the gods of grain and, in fact, the chariot races were done in honor to them. There was an altar in the circus dedicated to Consus, protector of grain, and on it was an inscription that read: “Consus, great council, Mars, in battle, mighty tutelar deities.” The fact that the arena was also dedicated to Mars — the god of war — indicated how violence and religion were merged together within this paradigm of ritual murder. Before the chariot races commenced there was a pompous procession of music and incense.

Animal sacrifices were also made. A parade of idol carrying took place from the Capitol to the Circus. Images of an owl, a peacock or thunderbolt were lifted up as attributes of the gods and carried on moving chariots embellished with gold and silver. Besides these were statutes of emperors who were deified. The “games” were not just a dedication to the gods who were in the spiritual world, but to the emperor who was declared a god. “Let high antiquity, O Caesar,” writes Martial, “lay down its pride; all its fame the arena offers to your eyes.” Tertullian makes mention of how the games were in dedication to the emperors who, as he wrote, were given the same praises as the gods:

“Who could excuse the outrage that you reckon any old dead person as equal to the gods? Indeed your kings are accorded the same sacred rites as the gods — grand vehicles to transport their statues, chariots, their likeness reclining on couches and chairs, wild beasts, and gladiatorial games.” (Ad Nationes, ch. x)

That the gladiatorial matches were ritual sacrifices is also demonstrated in the fact that the Romans would organize reenactments of mythological events in the Colosseum in which victims were slaughtered in order to abide by the mythological narrative. Events in the religious stories of the Romans were displayed and victims would be dressed as mythical characters who were, in accordance to the story, suppose to die. In one event a manufactured mountain was erected to represent Mount Etna where it was believed that Zeus trapped the monster Typhon. On top of the mountain was the victim, chained and half-naked, portrayed as either Prometheus or as Selurus, a famed criminal who terrorized the area around Mount Etna. One could see from his breathing — his chest elevating in terror — that he was horrified. The victim was surrounded by cages of wild beasts which were opened and the man torn to pieces. In another one of these reenactments, a victim was presented as the religious character Orpheus and fed to a bear. In another event a woman would be decorated as the mythological character Dirce, and fed to a panther. In doing these evil things the Romans were manifesting their mythologies into reality. Tertullian described the rituals of dressing up victims as gods before slaughtering them in the arena and mentioned how devoted the Romans were to these horrific events:

“When it comes to the gladiatorial shows, you are even more devout. Condemned criminals are dressed up as gods and then your gods dance about through the blood and gore as convicts act out the plots and fables. We have often seen a criminal dressed as your god Attis from Pessinum undergo public castration. And we have seen someone burned alive while dressed as Hercules.”

Dressing up the victims as gods is what the Aztecs would do to their ritual victims. As historian Lori Boornazian Diel explains:

“Such a sacrificial victim would have been dressed as a god and treated as the god’s incarnation on earth. The sacrifice of these godly impersonators was meant to mimic the original sacrifice of the gods in the primordial past and to provide that god more nourishment. For example, the image of the monthly ritual of the Tlacaxipehualiztli … shows a victim who has been dressed in the garb of Xipe Totec. His inevitable death will recreate the one the god had suffered in the primordial past.” (Diel, Aztec Codexes, p. 168)

That the Romans dressed their victims as gods and murdered them — Hercules is burned alive, Orpheus is eaten by a bear, etc. — and the Aztecs also dressed up their victims as gods to be killed, shows a similar pattern of terror in the reign of paganism. Today we see paganism becoming very popular, be it the worship of “mother earth,” or the revival of Nordic gods like Odin and Thor — with Identitarians and ethno-nationalists uplifting Thor’s Hammer. There seems to be little point to wonder what would be the result of such groups getting their way, when all we need to do is look at the story of history and know the end of the story.